Executive Summary

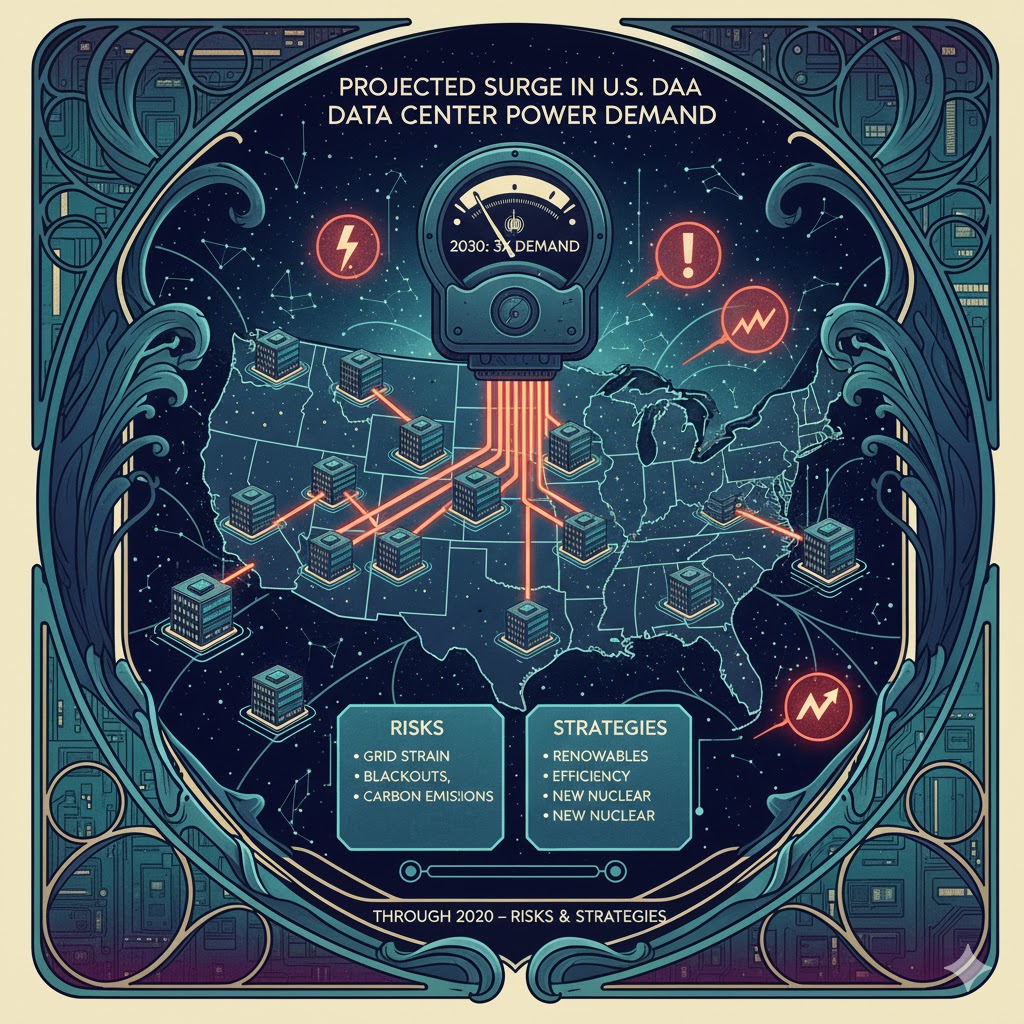

Data centers are poised to become one of the fastest-growing consumers of electricity in the United States over the next decade. Recent forecasts project U.S. grid power demand from data centers nearly tripling by 2030 (to roughly 134 GW), compared to 2024 levelsspglobal.com. This dramatic rise – driven largely by hyperscale cloud expansion and energy-intensive AI workloads – could push data centers’ share of U.S. power consumption to between 6.7% and 12% by 2028reuters.com, up from ~4% today. The boom presents significant risks across the power ecosystem, including grid congestion, carbon emissions, speculative load requests, cost burdens on ratepayers, and permitting delays. However, it also opens opportunities for strategic solutions.

This white paper provides a comprehensive analysis of the coming data center energy surge and its implications for major stakeholder groups. We synthesize the latest forecasts (e.g. S&P Global Market Intelligence’s 451 Research outlook) and expert research (DOE, IEA, etc.), then examine regional hotspots where demand will spike, key risks to infrastructure and sustainability, and mitigation strategies. Finally, we offer tailored guidance for data center operators, policymakers, investors, and energy analysts – from best practices in site selection and power procurement to policy incentives, investment frameworks, and modeling approaches. The goal is to inform evidence-based decisions that enable meeting data centers’ rising power needs sustainably and efficiently, without compromising grid reliability or broader climate goals. Clear takeaways and visual exhibits (forecast curves, regional demand charts, investment trends) are included to illustrate the challenges and opportunities ahead.

Background: Data Center Energy Trends

Over the past decade, data center energy consumption has undergone a rapid escalation after a period of efficiency gains. Historically, aggressive improvements in hardware efficiency and cooling had kept global data center electricity use relatively flat through the 2010s. However, the recent explosion of digital demand – especially from cloud computing and AI – has reversed that trend. The U.S. Department of Energy found that between 2017 and 2023, power demand from U.S. data centers more than doubled as AI servers and high-density equipment were deployedreuters.comreuters.com.

Globally, the International Energy Agency (IEA) now projects data centers’ electricity consumption will more than double from 2024 to 2030, reaching ~945 TWh/year (equivalent to Japan’s total power use)datacentremagazine.com. This surge is attributed to AI as “the most important driver of this growth”datacentremagazine.com. Indeed, AI and machine learning workloads require increasingly powerful chips and intensive cooling, pushing energy use sharply higherreuters.comreuters.com. Major cloud and social media companies are racing to build new “AI supercomputing” data centers, some of unprecedented scale – campuses exceeding 1 GW of capacity (as large as a nuclear reactor) are now on the horizonreuters.comreuters.com.

Crucially, these developments mean data centers are becoming a significant segment of national power demand. U.S. data centers consumed roughly 4% of U.S. electricity in 2023, but that share is climbing fastreuters.com. In certain regions like Northern Virginia – home to the world’s largest data center hub – data facilities already dominate local power load, prompting concerns about grid stress and community impacts. Without proactive measures, the energy footprint of the digital economy could pose challenges for grid reliability, costs, and climate targets. Policymakers in the EU have begun instituting efficiency requirements for data centers, but the U.S. currently lacks a unified strategyreuters.com. This paper provides context on these trends and delves into forward-looking forecasts to 2030, when the next wave of digital infrastructure build-out will be fully realized.

Soaring Demand: Forecasts & Modeling Through 2030

Recent forecasts converge on unprecedented growth in data center power requirements through 2030. In September 2025, S&P Global’s 451 Research released an updated U.S. data center power outlook that significantly raised its projections (reflecting an acceleration from even a few months prior)spglobal.com. Key findings from the 451 Research forecast include:

- Total U.S. Data Center Load (grid-supplied power for hyperscale cloud, colocation, and crypto-mining facilities) is expected to reach 61.8 GW by end of 2025, a 22% increase in just one yearspglobal.com. This implies roughly 50.5 GW was needed in 2024, meaning a jump of ~11.3 GW in new demand within 2025spglobal.com.

- Rapid growth continues: projected ~75.8 GW in 2026, ~108 GW by 2028, and ~134.4 GW by 2030spglobal.com. In other words, 2030 demand is nearly triple that of 2024 (almost +170% increase)spglobal.com. The demand trajectory is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: U.S. Data Center Grid Power Demand Forecast (2024–2030). The 451 Research outlook (S&P Global) predicts a rise from ~50 GW in 2024 to ~134 GW by 2030, nearly a threefold increasespglobal.comspglobal.com. This forecast covers utility-supplied power for hyperscale, colocation, and crypto mining data centers, excluding smaller enterprise-run server roomsspglobal.com.

Notably, this outlook excludes enterprise-owned data centers outside the hyperscale operatorsspglobal.com. Thus, actual total data center power usage (if one included on-premises corporate data centers) would be even higher. Artificial Intelligence is identified as the “dominant near-term driver” of these load increasesspglobal.compfie.com. The training and operation of advanced AI models require vast computing power; the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) estimates U.S. power demand for AI alone could rise from ~5 GW in 2023 to over 50 GW by 2030spglobal.comspglobal.com. In other words, AI-related data center loads may grow tenfold this decade, accounting for a large portion of the overall forecast demand. The training of frontier AI models is already so power-hungry that individual training runs can draw 100–150 MW each, potentially reaching 1–2 GW per run by 2028 and up to 4–16 GW by 2030 for the largest modelsspglobal.com. Such figures underscore why utilities and grid planners are bracing for unprecedented loads concentrated in AI data center clusters.

Forecasting data center energy use is challenging given the uncertainties in technology and deployment. Different scenarios show a range of outcomes by 2030. A DOE-backed study by Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (Dec 2024) projected U.S. data centers could consume between 74 GW and 132 GW of power (annual average basis) by 2028, depending on AI chip adoption ratesreuters.com. This corresponds to 6.7%–12% of total U.S. electricity consumption by 2028reuters.com – a range that aligns with the high end of the 451 Research forecast when converted to comparable terms. Meanwhile, global forecasts by investment analysts are similarly striking: for example, Goldman Sachs expects global data center power demand to rise up to +165% by 2030 (relative to 2022) under an AI-driven scenariogoldmansachs.com, and McKinsey estimates keeping pace with compute demand worldwide could require $6–7 trillion in data center investment by 2030mckinsey.com. These projections, though varying in magnitude, all point to extraordinary growth. Figure 1 above captures the consensus trend: a steep climb through 2030.

Importantly, many forecasts are being revised upward frequently as new data emerges. 451 Research’s mid-2025 update was higher than its outlook just earlier that yearspglobal.com, reflecting larger-than-expected build plans. Likewise, the Berkeley Lab study introduced a high scenario (~12% of U.S. power by 2028) that starkly contrasts the IEA’s more conservative global view (+15% energy use by 2030 in one estimate) – highlighting the role of assumptions about efficiency gains vs. new demandsciencedirect.commitsloan.mit.edu. Given the pivotal impact of AI adoption rates, efficiency improvements, and policy interventions, energy analysts caution that actual outcomes could swing higher or lower. In all cases, however, the direction is clear: without dramatic efficiency breakthroughs, data centers will constitute a major new category of electricity load by 2030, rivaling industrial sectors in scale. This raises pressing questions about where this demand will materialize and how the power sector will accommodate it.

Regional Hotspots: Where Demand Will Spike

Data center growth is not uniform across the U.S. – it is highly concentrated in certain regions, creating acute local impacts. According to 451 Research’s forecast, the top two states (Virginia and Texas) will far outpace others in data center power demand by the mid-2020sspglobal.com. Figure 2 shows a breakdown of projected 2025 data center load by state, illustrating the regional “pressure points”:

Figure 2: Projected Data Center Grid Power Demand by U.S. State in 2025spglobal.comspglobal.com. Virginia (home to Northern Virginia’s massive data center cluster) and Texas (with its large crypto mining and cloud campuses) are by far the largest, followed by Oregon and a group of states (AZ, GA, OH, CA, IL, IA) each expecting 2–4 GW of demand.

- Northern Virginia (Loudoun/Prince William Counties) – often dubbed “Data Center Alley” – remains the single largest hub in the world. Virginia’s data center load is forecast at ~12.1 GW in 2025, up 30% year-over-year from ~9.3 GW in 2024spglobal.com. This astonishing scale (comparable to the entire power demand of some small countries) stems from dozens of major campuses for Amazon Web Services, Microsoft, Google, Meta, and many colocation providers in the Ashburn area. The strain on Dominion Energy’s grid in Northern Virginia has already led to warnings of multi-year interconnection delays – connecting a new data center there can now take up to six or seven years due to grid capacity constraints, up from ~4 years previouslydatacenterknowledge.com. Virginia’s dominance will likely persist through 2030, although growth may be tempered by these grid limits and efforts by operators to expand elsewhere.

- Texas is the #2 state and rising quickly. Forecasts show Texas data centers drawing ~9.7 GW in 2025 (up from <8 GW in 2024)spglobal.com. Contributing factors include crypto-mining operations, which flocked to Texas for its relatively cheap electricity and deregulated ERCOT market, as well as new hyperscale cloud builds (e.g. around Dallas/Fort Worth and in West Texas). Texas benefits from abundant land and growing renewable generation, but parts of the state (e.g. the Permian Basin region) have limited transmission infrastructure. Indeed, some smaller cities in West Texas are seeing data center projects that rely on on-site power (using ample local natural gas) due to grid limitationsdatacenterdynamics.com. Texas policymakers and ERCOT have introduced stricter interconnection rules for large loads, and require big users to ride-through grid disturbances, to manage the influxreuters.com.

- Oregon (especially the Portland/Hillsboro area and central Oregon) is another major cluster, with expected ~4 GW by 2025spglobal.com. The cool climate and robust hydroelectric power make Oregon attractive. It hosts large cloud data centers (e.g. Google in The Dalles, Facebook in Prineville) and semiconductor firms’ compute farms. While Oregon’s absolute demand is lower than VA or TX, it is significant regionally – and continues to grow from ~3.5 GW in 2024spglobal.com.

- Second-tier hubs around 3 GW each by 2025 include: Arizona (Phoenix area’s data center corridor), Georgia (Atlanta region, plus Google’s sizable footprint), Ohio (Columbus area, a booming hub for cloud facilities), California (primarily Silicon Valley/Santa Clara, though constrained by high costs and limited power in some areas), Illinois (Chicago area is a long-standing data center market), and Iowa (Des Moines area with large Facebook, Microsoft campuses)spglobal.com. Each of these is projected in the ~2.3–3.2 GW range for 2025spglobal.com. Ohio’s growth is particularly noteworthy – Columbus has become a strategic location with major cloud campuses, and 451 Research notes “significant growth in Ohio” in its outlookspglobal.com. Ohio is aggressively courting data centers with tax incentives, though recent utility tariff changes (discussed later) have introduced new costs for power.

- Emerging markets: To alleviate saturation in traditional hubs, operators are scouting less tapped areas. Idaho, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and smaller metros in Texas are cited as seeing increased interestspglobal.com. These locations often offer “stranded” or underutilized power (e.g. near aging power plants or regions with excess generation) and are pursuing “alternative energy generation opportunities”spglobal.com. For example, Louisiana landed a massive Meta (Facebook) data center project, drawn by available land and potential renewable power, and Idaho has attracted enterprise data centers leveraging its hydro and industrial power capacity. While each of these markets will remain relatively small by 2030, collectively they represent a trend of geographic diversification – a deliberate strategy by operators to find sites with open grid capacity and favorable costs.

The regional concentration of demand means local grids will face intense stress in certain pockets. Two of the largest power markets illustrate contrasting approaches: PJM (Mid-Atlantic), which covers Northern Virginia, is grappling with backlogs of new data center load and is turning to tools like capacity auctions and demand response programs to manage growthreuters.com. Meanwhile ERCOT (Texas), experiencing a boom in both data centers and renewable generation, has implemented new reliability standards for large loads and is incentivizing flexible consumption (e.g. rewarding data centers that can modulate usage during peak periods)reuters.com. Both regions underscore that where data centers locate has major implications for grid planning – clustering in one area can overwhelm local infrastructure, while spreading to new areas can require building transmission and generation anew.

In summary, Virginia and Texas stand out as epicenters of data center energy demand in the U.S. now and through 2030, with Oregon and a half-dozen other states forming a second tier of high activity. This concentrated growth creates “pressure points” – areas where grid congestion, land use conflicts, and environmental impacts of data centers become especially pronounced. These will be the proving grounds for how effectively stakeholders manage the surge in demand. The next sections delve into the specific risks arising from this growth and the strategies to address them, often using lessons from these hotspot regions.

Key Risks of Rapid Load Growth

The projected leap in data center power demand brings multiple risks that must be navigated. These risks span technical, economic, and environmental domains, and they affect different stakeholders in distinct ways. Here we analyze the most critical challenges:

1. Grid Congestion & Infrastructure Strain

Perhaps the most immediate risk is grid congestion – the inability of electric infrastructure to deliver power to data centers quickly enough or in sufficient volume. Many utilities and grid operators are overwhelmed by interconnection requests for new data center loads, leading to lengthy delays for hooking up facilities. For example, in Northern Virginia (PJM grid), some new data centers are waiting 5–7 years for necessary substation and transmission upgradesdatacenterknowledge.com. Bloomberg reported those Virginia connection timelines have nearly doubled (from ~3–4 years to up to 7) due to the surge in requestsdatacenterknowledge.com.

Several factors drive these delays:

- Capacity Constraints: In prime locations, the existing grid (substations, transformers, transmission lines) is near exhaustion. The scale of data center loads – often tens or hundreds of MW per site – can outstrip local grid capacity. Utilities like Dominion Energy (VA) and AEP Ohio have been caught off-guard by the sheer volume of demand, necessitating massive grid build-outs. AEP noted it had 190 GW of data center load in its interconnection queue across its territory (an unrealistic figure equal to 5× its current system size) before scrubbing speculative projectsspglobal.com.

- Permitting & Construction Lead Times: Building new power infrastructure (high-voltage lines, substations, generation plants) is a multi-year process often slowed by permitting, environmental reviews, and supply chain challenges. As consultancy E3 warned in a Virginia grid study, the pace of siting and permitting new infrastructure will “very likely act as a constraint on data center growth in the near to medium term”reuters.com. In short, data centers can be constructed in 18–24 months, but the grid upgrades to supply them can take far longer, creating a mismatch.

- Queue Backlogs: Regional grid operators (ISOs/RTOs) were already swamped with new generation (especially renewable) interconnection requests; now data center load requests add to the logjamreuters.comreuters.com. Processing these in serial fashion has created multi-year queues. Efforts are underway to reform interconnection processes, but relief will not be immediate.

The risk is that grid bottlenecks could stall data center projects, cause some planned capacity to be deferred or cancelled, and limit growth in key markets. In fact, we are seeing early signs: some utilities report declining or deferred interconnection requests as developers realize certain locations are full. The 451 Research report noted AEP Ohio cut its active data center pipeline from 30+ GW to 13 GW in 2023datacenterdynamics.com, after a new rule forced removal of projects that weren’t firmly committed. This indicates many proposed projects were likely speculative placeholders (see below) that the grid couldn’t accommodate all at once.

Additionally, grid strain poses reliability risks. Concentrated data center clusters can present single points of failure: if a key substation or transmission corridor is maxed out, an outage or delay in upgrades there could jeopardize hundreds of MW of load coming online. There is also concern about synchronous demand spikes – for instance, if many data centers in an area ramp up simultaneously (say, to handle an AI workload surge), it could stress generation supply. Grid operators are responding with measures like requiring large data centers to have ride-through capability (so they don’t trip off during grid disturbances)reuters.com and using demand response programs to incentivize flexibilityreuters.com.

In summary, insufficient grid supply and congestion is a top threat to meeting the forecasted demand. Without intervention, connection delays and power shortfalls could become a major bottleneck for data center growth.

2. Speculative Load and Overbuild Risk

The gold-rush mentality in some regions has led to “speculative” load requests – developers or customers reserving far more power than they will realistically use in the near term. This creates risks of overbuilding infrastructure and stranding costs. Utilities must plan capacity for the peak loads requested, but if those loads don’t materialize (or are delayed), the investments can become underutilized – with costs potentially passed to other ratepayers.

This issue came to a head in Ohio in 2023. American Electric Power (AEP) testified that data center companies had flooded its Ohio interconnection queue with tens of gigawatts of requests, many duplicative or tentative. In response, the Ohio regulators approved a new “data center tariff” that requires large data center customers to pay for 85% of their subscribed capacity, regardless of actual usespglobal.comspglobal.com. This move was explicitly to “cull duplicative or speculative requests”spglobal.com and protect other customers from bearing costs of infrastructure built for phantom loads. The result was immediate: as noted, AEP removed the most speculative 17+ GW of projects from its plans, effectively halving its pipeline to focus on the serious, committed projectsdatacenterdynamics.com.

This highlights a broader risk: without proper incentives or penalties, data center developers might hoard grid capacity (locking in more MW than needed, just in case), leading utilities to chase potentially illusory demand. The cost of misjudging this could be high – large power upgrades or new power plants built for loads that never fully ramp up would create stranded assets. Those costs could fall on either the utility’s shareholders or on ratepayers (hence the Ohio Consumers’ Counsel pushed for the protective tariff)spglobal.com.

Other regions are taking note. Dominion Energy in Virginia similarly proposed a special high-load rate class in 2024 to ensure data centers pay their fair share of grid costs and to reduce the burden on residential customersreuters.com. Dominion had an astonishing 40 GW of data center capacity under contract by end of 2024 (including planned projects), up from 21 GW just six months priorreuters.com – a jump that could indicate many new deals signed, but also possibly optimistic reservations. Dominion’s proposed tariff aimed to prevent regular customers from subsidizing the huge investments needed for these data center connections.

The risk of speculative overbuild therefore intersects with cost and equity concerns (discussed next). To mitigate this, more utilities and regulators may implement “use-it-or-pay” structures, requirement of financial guarantees or letters-of-credit for requested capacity, and regular pruning of interconnection queues. While these measures protect the grid and ratepayers, they could also slow down or force consolidation of data center plans, which stakeholders need to anticipate.

3. Cost Burdens and Ratepayer Impact

The scale of new data center load growth requires equally large investment in generation and grid infrastructure. Who pays for these investments is a contentious question. If not managed, there is a risk that the cost burden falls on general ratepayers, causing electricity bills to rise for households and other businesses who see no direct benefit from data centers.

For instance, Dominion Energy’s plan to support Northern Virginia data centers involves major capital expenditures on new transmission lines and renewable generation. Dominion signaled intent to raise electricity rates for its broader customer base to fund these expansionsreuters.com – a proposal that raised concern among consumer advocates. The Virginia State Corporation Commission and policymakers have to balance economic development benefits of data centers (jobs, tax base) against the potential rate impacts on millions of customers if utility costs skyrocket.

As noted earlier, Ohio’s regulatory action was driven by the fear of “underused investments to serve the data-center industry” leaving ordinary customers footing the billspglobal.com. By forcing data centers to cover 85% of their subscribed capacity costs, Ohio aimed to shield residential and small commercial users from subsidizing idle capacity.

Even with such measures, utilities are dramatically ramping up spending: AEP announced a $16 billion increase to its capital plan (to total $70B over five years) partly due to firm data center demandspglobal.com. Other utilities like PSEG and Exelon (serving areas with data center growth) have similar multi-billion-dollar grid plans. If data center growth falters or efficiency gains reduce their actual usage, there’s a risk utilities could over-invest. Conversely, if growth continues but costs are not properly assigned, average customers in high-data-center regions could see higher rates to support the needed infrastructure.

There is also a cost burden in terms of market power prices: Large new constant loads can push up demand in wholesale markets, potentially raising prices unless new generation is built in tandem. The DOE noted overall U.S. power demand reached a record high in 2024 and will hit new peaks next year, with data centers and electrification as key driversreuters.com. If generation supply doesn’t keep up, energy prices could rise broadly.

In summary, managing the cost burden is crucial. The risk of public backlash against data centers grows if they are perceived to be driving up neighbors’ utility bills. Transparent tariffs, developer contributions to grid upgrades, and creative rate design (like time-of-use rates that reward off-peak data center consumption) will be key to ensure costs are allocated fairly.

4. Carbon Emissions and Sustainability Challenges

The flip side of booming data center electricity use is the potential for a massive increase in carbon emissions if that electricity is not clean. Even as hyperscale operators pledge 100% renewable energy and carbon-neutral operations, the reality is complex: marginal power demand from data centers may still be met by fossil-fueled generation, especially in the near term as grids decarbonize.

Research by Morgan Stanley indicates that, at current trajectories, global data centers will emit about 2.5 billion metric tons of CO₂ cumulatively by 2030datacenterdynamics.com. That represents ~40% of the U.S.’s annual emissions – a huge climate footprint concentrated in the digital sectordatacenterdynamics.com. This is despite the leading operators’ climate pledges; their rapid expansion in AI and cloud is simply outpacing the greening of gridsdatacenterdynamics.com.

Specific emission-related risks include:

- Grid Power Mix: Many of the hottest data center markets (e.g. Northern Virginia, Georgia, Texas) still have significant fossil generation. As data center load rises, unless matched by new zero-carbon generation, the absolute emissions from powering these facilities will grow. The IEA warns that data centers could become a major source of demand growth that, if not managed, undermines decarbonization progressdatacentremagazine.com. For example, Virginia’s grid has been heavily coal- and gas-based, so adding 12 GW of data center load without equivalent clean power would generate substantial CO₂.

- Backup Generation: Data centers rely on backup diesel generators for reliability, which can be heavy polluters if used frequently. In grids with reliability issues, there’s risk of more generator runtime. Moreover, the trend toward on-site generation (see below) often means onsite gas turbines or fuel cells that, while improving grid resilience, still emit carbon on-site if fueled by natural gas. AEP’s deal to deploy up to 1 GW of Bloom Energy fuel cells for data centers, for instance, provides power resilience but is powered by natural gas (unless hydrogen is used)spglobal.com. Widespread use of on-site fossil solutions could simply shift emissions from the grid to the facility level.

- Embodied Carbon: The construction of thousands of megawatts of new data center capacity (concrete, steel, equipment manufacturing) carries an embedded carbon cost. While not part of operational grid demand, it’s part of the sector’s overall climate impact. Hyperscalers are exploring “green concrete” and low-carbon building materialsdatacenterdynamics.com to mitigate this, but it remains a concern.

- Water and Heat: Although not carbon, sustainability risks include massive water usage for cooling in some facilities (which can stress local water supplies) and waste heat generation. In areas facing drought or heatwaves, large data center water consumption or heat output could become flashpoints with communities – potentially causing permitting or operational constraints.

The risk is that unchecked growth could make data centers a lightning rod in climate policy debates, especially if public perceives “big tech” as consuming huge energy and emitting carbon while everyone else is urged to conserve. Regulators could respond with mandates (e.g. stricter efficiency standards, renewable usage requirements, or even moratoria as seen in parts of Europe) if emissions climb too fast.

On the flip side, there is an opportunity to drive decarbonization solutions: Morgan Stanley’s analysis suggests the data center boom is already spurring investments in clean power development and efficiency tech to mitigate emissionsdatacenterdynamics.com. Many hyperscalers are among the world’s largest buyers of renewables – Microsoft alone has contracted ~34 GW of clean energy capacitydatacenterdynamics.com and companies like Meta have signed deals for entire nuclear plant outputs to ensure carbon-free supplydatacenterdynamics.com. The key will be aligning the timing and scale of renewable and zero-carbon generation buildout with the data center load growth. A gap between the two (load outpacing clean supply) is a risk for emissions.

In summary, emissions risk is inherent in the growth unless mitigated by aggressive clean energy procurement and technological innovation (efficiency, battery storage, etc.). Data centers could contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 in worst-case scenarios, but they could also drive new clean energy solutions if managed well.

5. Permitting Delays & Community Opposition

The speed of data center expansion can clash with the slower pace of government approval processes, leading to permitting delays for both data center construction and the required energy infrastructure. This risk manifests in several ways:

- Power Infrastructure Permitting: As noted, building a new high-voltage transmission line or large substation faces lengthy permitting – environmental impact assessments, public hearings, rights-of-way acquisition, etc. If regulators and utilities cannot streamline these processes, critical projects could lag behind the needed timeframe, delaying data center projects or constraining operations. Federal and state authorities are looking at ways to fast-track transmission for renewables and large loads, but progress is incremental.

- Data Center Permitting & Moratoria: At the local level, some communities have started pushing back on data center growth. Issues cited include noise (from cooling fans), diesel generator emissions, water usage for cooling, and land use concerns. While the U.S. has not yet seen widespread moratoria, there have been instances: e.g., in 2022, some towns in Northern Virginia considered pauses on new data center approvals pending noise and zoning reviews. Internationally, places like the Netherlands, Ireland, and Singapore temporarily paused new data center projects to reassess policies due to power and land constraints – indicating what could happen in U.S. hotspots if strain becomes too high. Community opposition could especially rise if blackouts/brownouts or rate hikes are blamed (rightly or wrongly) on over-expansion of data centers.

- Supply Chain & Labor Delays: A softer aspect of “permitting” is simply the availability of skilled labor and critical equipment (e.g. transformers) to execute projects on schedule. The current construction boom (including renewable energy projects) has led to transformer shortages and a tight construction labor market. This can act as a drag, effectively delaying completion even if permits are in hand.

The net effect of these factors is the risk of timeline slips. If data center capacity comes online before supporting infrastructure (or vice versa, if infrastructure is ready but data center is delayed by local permits), it creates mismatches and financial stress. For example, a cloud operator might build a data center expecting power by a certain date, but if a transmission upgrade is two years late, that facility might sit idle – a costly delay. Or a utility might invest in upgrades expecting a data campus to materialize, but if local opposition stops the project, the utility’s investment could become stranded.

Mitigating permitting risk requires proactive planning and community engagement. Some states are now explicitly planning for data center growth in their energy roadmaps. For instance, Virginia’s regulators commissioned studies on grid strain and are contemplating policy changes to better integrate data center needsreuters.com. Meanwhile, data center firms are increasing outreach – showcasing economic benefits to communities and addressing concerns (e.g. designing to minimize noise, using air-cooled systems to reduce water use, agreeing to sustainability measures). Policymakers can help by creating clearer guidelines and one-stop permitting processes for critical infrastructure.

In summary, the major risks – grid congestion, speculative load, cost burden, emissions, and permitting hurdles – are interrelated. Congested grids and slow permits can feed speculative behavior (as developers jockey for limited capacity), which in turn can increase costs and local pushback. Rising emissions without adequate mitigation could trigger regulatory responses that affect permitting or operating costs. Recognizing these linkages, the next section discusses strategic solutions and best practices to tackle these challenges head-on, in a way that balances stakeholder interests and ensures demand can be met sustainably.

Strategies for Sustainable Demand Growth

Meeting the surging data center power demand through 2030 will require a portfolio of strategies. No single solution can resolve the multifaceted risks – instead, coordinated efforts by operators, utilities, policymakers, and investors are needed to enable sustainable growth. Below we outline key strategies and best practices, which will be further tailored to each stakeholder group in the following section.

1. Proactive Infrastructure Planning & Investment: Long-term planning is crucial. Utilities and grid operators should incorporate data center growth into their load forecasts and capacity expansion plans (many already are). This means scheduling timely upgrades to transmission and distribution networks in known hot zones (e.g. Northern Virginia, Dallas area, Phoenix) and accelerating generation development (especially clean energy) to supply the new load. Joint planning between data center operators and utilities can help pinpoint needs – for instance, identifying locations where new substations or high-voltage lines could unlock large amounts of capacity. In some cases, utilities are adjusting their investment strategies: as noted, AEP increased its 5-year capex plan to $70B partly for data centersspglobal.com, and others are following suit. Such investments, if aligned with actual demand, can alleviate grid congestion before it becomes acute.

2. Smarter Interconnection Processes: To combat speculative requests and long queues, regulators can reform interconnection rules. Approaches include requiring deposits or security payments for requested capacity (to ensure seriousness), batch processing of requests (to study multiple projects together and build shared upgrades), and “first-ready, first-served” approaches that reward projects that are prepared to move forward. As seen in Ohio, special tariffs or contracts that commit data centers to their demand can discourage overallocationspglobal.com. PJM and other RTOs are already overhauling their interconnection study processes to expedite projects – continuing this momentum will be key to get needed infrastructure in place faster.

3. Geographical Diversification: Both operators and policymakers can pursue strategies to spread out the load and avoid over-concentration. For operators, that means site selection in areas with available power headroom (perhaps a bit off the beaten path, but still meeting other criteria). We see this happening with companies exploring sites in e.g. Idaho, Oklahoma, and other “edge” marketsspglobal.com. For policymakers, it could mean incentivizing data centers to locate in regions with excess capacity – for example, near retiring coal plants that have grid infrastructure in place or in regions eager for economic development where the grid can be upgraded with public support. Tax incentives or faster permitting in these alternative locations can nudge development away from already strained hubs. This reduces grid congestion and brings jobs to new areas, a win-win if done thoughtfully.

4. On-Site Generation & Microgrids: An emerging trend is the use of on-site power solutions to supplement or even replace grid supply for data centers, especially when grid timelines are too slow. On-site generation can include natural gas turbines, fuel cells, solar+storage, even small modular reactors or other innovative systems. For instance, AEP’s arrangement to provide 100 MW of Bloom Energy fuel cells (with option up to 1 GW) for data centers is one “bridge solution” while grid upgrades catch upspglobal.com. In West Texas, some data centers are tapping direct gas generation in the Permian regiondatacenterdynamics.com. Microgrids that integrate these local resources with the utility feed can offer both resilience and capacity relief – if the grid is constrained, the data center can run partially islanded on its own generation. Over time, cleaner on-site options (like biogas or hydrogen fuel cells, small nuclear, etc.) could provide large reliable power with lower emissions. The IEA advocates microgrid and distributed energy solutions as a way to leapfrog grid bottlenecksdatacentremagazine.comdatacentremagazine.com. That said, on-site generation must be used carefully – coordination with the grid is needed to maintain stability, and emissions from on-site fossil generators must be addressed. Still, strategic deployment of on-site power is proving to be a practical tool to keep projects on track despite grid delays.

5. Energy Efficiency & Demand Flexibility: A cornerstone to sustainable growth is making sure each data center uses power as efficiently as possible and can be flexible with timing of its usage. Efficiency measures (e.g. advanced cooling, AI-optimized workload scheduling, higher server utilization rates) can bend the growth curve downward from what it otherwise would be. The good news is that operators are intensely focused on efficiency: new builds often boast power usage effectiveness (PUE) ratings of 1.2 or lower (meaning very little overhead energy beyond IT equipment), and liquid cooling and other innovations aim to reduce cooling power further. On the IT side, more efficient chips and better software can perform the same work with less energy. The IEA and DOE both emphasize efficiency as a key lever – noting that identifying what specifically drives energy growth (e.g. GPU deployments) can highlight where efficiency efforts should targetreuters.com.

Demand flexibility refers to data centers adjusting their load in response to grid conditions. Traditionally, data centers are considered inflexible (they run 24/7 at high utilization). But emerging approaches may change that: for example, non-mission-critical workloads (like certain AI training jobs or batch data processing) could be scheduled at times when renewable energy is abundant or power prices are low, effectively acting as demand response. Some operators are exploring making their backup systems available to support the grid at peak times (for instance, using batteries to draw less grid power or even inject power for a short duration). Grid operators like CAISO (California) have introduced incentives for flexible loads and time-of-use rates that data centers can take advantage ofreuters.com. If data centers, even partially, become “interruptible” or shiftable loads, it can greatly ease their integration and reduce the need for peaking power plants.

6. Renewable and Clean Energy Procurement: To tackle the emissions risk and ensure sustainable power, data center companies will need to continue and expand their role as major buyers of clean energy. This means signing large power purchase agreements (PPAs) for solar, wind, hydro, and possibly emerging sources like geothermal or next-gen nuclear. Many hyperscalers are aiming for 24×7 carbon-free energy – matching every hour of consumption with carbon-free generation. Achieving this at the scale of 100+ GW by 2030 is daunting, but their investments are trending up. We should see more innovative deals, such as direct procurement from new nuclear plants (e.g. small modular reactors slated for late 2020s) or energy storage projects to firm renewable supply. Policymakers can assist by facilitating corporate access to wholesale markets and by offering green tariff programs via utilities. The net effect would be that even if data center load triples, its net carbon impact is minimized through parallel growth in clean energy supply. As Morgan Stanley’s report suggests, the data center industry’s expansion is already “increasing investments in clean power development” as an inherent responsedatacenterdynamics.com. Aligning incentives to continue this trend is key.

7. Policy and Regulatory Tools: Government at federal, state, and local levels can deploy various tools: incentives (tax credits for energy-efficient data centers, grants for site development in target regions), standards (e.g. mandating new data centers meet certain efficiency or backup power emissions standards), and planning mandates (requiring utilities to include data center scenarios in resource plans). For example, states could implement something akin to the EU’s upcoming requirement for data center energy reporting and waste-heat reuse – encouraging facilities to contribute to grid and community needs (like district heating) to improve overall sustainability. On the regulatory front, tariffs like Ohio’s or Dominion’s proposed high-load rate can be expanded to ensure fair cost distributionspglobal.comreuters.com. Also, streamlining permitting (perhaps designating some data center and power projects as critical infrastructure with faster review) can mitigate delays. The federal government’s involvement – through DOE studies and potential funding (as hinted by discussions of leveraging data centers for grid battery storage, small reactors, etc.reuters.com) – could play an increasing role in catalyzing solutions.

In summary, mitigating the risks and meeting demand sustainably will require a concerted strategy: build infrastructure ahead of need, enforce realistic planning (avoid hype-driven overbuild), use technology to enhance efficiency and flexibility, and align growth with clean energy development. The next section breaks down specific recommendations for each stakeholder group, recognizing their unique roles in implementing these solutions.

Stakeholder Perspectives & Recommendations

Different stakeholders in the data center and energy ecosystem will need to take tailored actions to manage the coming surge. Below, we provide focused guidance for data center operators, policymakers, investors, and energy analysts, highlighting strategies and best practices most relevant to each.

For Data Center Operators

1. Smarter Site Selection: Choosing the right location is paramount. Prioritize sites with robust power availability and expansion potential – for example, areas with existing underutilized power plants or substations, regions actively adding renewable generation, or campuses adjacent to large transmission nodes. Avoid “power dead-zones” where the grid is already maxed out unless you plan to invest in on-site generation. Increasingly, operators are seeking sites near energy sources (e.g. near wind/solar farms or even at hydro dam locations) to ensure adequate supplydatacentremagazine.com. Also consider climate and environmental factors: cooler climates can reduce cooling loads, and areas outside extreme drought can alleviate water risk.

2. Early Utility Partnership: Engage with the local utility or grid operator early in the development process. Share your load requirements transparently and explore joint solutions – such as the utility building a dedicated substation or feeders for your campus, with costs shared or rate-based appropriately. Large operators are now signing electric service agreements well before construction, effectively reserving capacity (with financial commitments) to give utilities confidence to investspglobal.com. Be prepared to provide letters of credit or take-or-pay contracts as needed (similar to what Ohio’s tariff requiresspglobal.com) – this secures your project’s place in queue and helps avoid delays due to speculation concerns.

3. Power Procurement & Renewables: Strengthen your power procurement strategy beyond just buying from the grid at retail. Diversify with long-term PPAs for renewable energy to hedge cost and ensure sustainable supply. Many operators use a mix: direct utility supply for baseline load and supplement with PPAs or even direct wholesale market purchases for additional needs or renewables. For those with sustainability goals, strive for 24/7 carbon-free energy sourcing – e.g., pairing daytime solar with nighttime wind or battery storage, or leveraging emerging clean firm power (nuclear, geothermal) for around-the-clock coverage. Not only does this reduce emissions, it can improve resilience and public image.

Additionally, consider participating in demand response or capacity programs: e.g., if your data center can provide interruptible load or run on backup during grid peaks, you might earn revenue and help the grid (some operators have successfully done so in ERCOT and PJM programs). This kind of grid-service procurement can turn your energy strategy into a competitive advantage.

4. Embrace On-Site Energy Solutions: Equip new facilities with provisions for on-site power generation and storage. This might include designing space for solar panels on rooftops or campus grounds, battery energy storage systems (BESS) for backup and peak shaving, and quick connections for mobile generators or future fuel cells. On-site microgrids can insulate you from grid outages and, as noted, potentially allow new builds to proceed where the grid is constrained. Given trends, it’s wise to invest in cleaner on-site tech: for example, battery + renewable + fuel cell hybrids instead of solely diesel gensets. Some operators are already piloting using battery UPS systems to not just provide backup, but also to smooth power usage and participate in energy markets (earning back some cost). Being at the forefront of on-site energy innovation will not only reduce risk of downtime but can also address community concerns about emissions and noise (e.g., batteries are silent and emission-free in operation).

5. Advanced Energy Management & Efficiency: Continue to push the envelope on energy efficiency within your facilities. Aim for world-class PUE (power usage effectiveness) by leveraging the latest cooling technologies: liquid cooling for high-density racks, outside-air economization where climate allows, AI-driven cooling controls that adjust cooling output dynamically to IT load, etc. Reducing cooling and auxiliary loads directly cuts your power demand and costs. IT-side efficiency is just as important: optimize server utilization (through virtualization and workload management) so that compute per watt is maximized. Invest in next-gen servers and accelerators that deliver better performance per watt (for instance, newer AI chips or photonic interconnects can reduce energy per computation).

Also, explore flexible workload scheduling to improve your power profile. For example, if you have AI training jobs that can run anytime within a week, schedule them when electricity is cheapest or when renewable generation on the grid is high (some companies call this “renewables load shifting”). This flexibility could become a criteria in how you design software and data center operating procedures, effectively aligning compute with energy availability.

6. Community Engagement & Transparency: Given the growing public scrutiny, operators should proactively engage with communities and local governments. Be transparent about your power needs and plans to mitigate impacts (like grid upgrades you’re funding, or renewable energy you’re adding). Work with communities on issues like noise reduction (e.g., building berms or sound walls, using quieter cooling tech), traffic (for construction), and emergency planning (so they know what happens if grid power is tight – e.g., you’ll fire up generators, etc., and how you’ll minimize any disturbance). Some leading operators publish sustainability reports for their data centers, detailing energy and water usage and carbon footprint. This transparency can build trust and head off opposition that could lead to permitting delays. Furthermore, consider community benefit initiatives: for instance, using waste heat from data centers to support local heating needs, or investing in local workforce training. These efforts can change the narrative from “data centers strain our grid” to “data centers bring investment and innovation to our area.”

By adopting these strategies, data center operators can ensure they have reliable, cost-effective, and clean power to fuel their growth, while also being good grid citizens and community partners. The next stakeholder – policymakers – plays a critical role in setting the framework within which operators make these choices.

For Policymakers and Regulators

1. Holistic Infrastructure Planning: Policymakers should integrate data center growth into state and regional infrastructure plans. Identify future high-demand zones (in consultation with utilities and industry) and proactively plan needed grid upgrades (transmission, substations) and generation for those areas. This could mean tasking state energy offices or commissions to do scenario studies (like Virginia did with E3’s report on grid strainsreuters.com) and then aligning state infrastructure budgets or utility resource plans accordingly. Consider establishing special development zones for data centers where the state helps coordinate permitting of new lines or pipelines, etc., to support them. A holistic view can prevent reactive, piecemeal responses later.

2. Streamline Permitting and Reduce Red Tape: Time is of the essence. Review and reform permitting processes at the state and local level for both data centers and associated energy infrastructure. This could include creating a fast-track or one-stop permitting program for projects that meet certain criteria (for example, data center projects that come with their own renewable energy supply, or grid projects that increase capacity in designated zones). Ensure agencies coordinate – e.g., have the environmental regulators, utility commission, and local zoning authorities communicate early on big projects so that one approval doesn’t languish waiting on another. States might also look at legislation to expedite critical grid projects, perhaps by limiting the length of review periods or providing model zoning ordinances for data centers (to avoid each locality reinventing the wheel). The key is to shorten the timeline for bringing new capacity online without sacrificing essential environmental and community protections.

3. Smart Tariffs and Rate Structures: Regulators (public utility commissions) should consider implementing tariffs that allocate costs fairly and send proper signals. Ohio’s example of a data center rider requiring payment for unused reserved capacityspglobal.com is one model – it discourages over-reservation and protects other ratepayers. Similarly, Dominion’s proposed high-load rate class in Virginia aims to charge data centers in proportion to the infrastructure costs they impose, easing residential burdensreuters.com. Commissions should evaluate such mechanisms, perhaps adopting demand charges or cost trackers specifically for large new loads. Also, consider time-of-use rates or critical peak pricing for data centers – incentivize them to flatten their load or use backup during grid peaks. If structured well, this can encourage the flexibility on the operator side (as mentioned earlier). Transparent, fair tariffs will be crucial to maintaining public support: ratepayers should see that data centers are paying their way and even providing grid benefits, rather than being subsidized.

4. Incentivize Sustainable Practices: Use policy levers to encourage data centers to be built and operated sustainably. For instance, offer tax credits or abatements for projects that meet certain energy efficiency standards (like a PUE below a threshold) or that incorporate on-site renewables. Some states already give sales tax exemptions on data center equipment – these could be tied to meeting green criteria. Consider requiring renewable energy procurement as part of large data center deals (for example, if a company wants a tax break, they must source X% of their power from in-state renewable projects). Another idea is to facilitate waste heat reuse: provide grants or partner with data center operators to capture their waste heat for use in district heating or industrial processes, turning an environmental concern into a benefit.

Policymakers can also support R&D and pilots for new solutions – e.g., funding demonstrations of fuel cell or advanced battery systems at data centers, or exploring recycling of servers to reduce e-waste and embodied carbon. Given data centers will be long-term infrastructure, building sustainability in from the start via policy will pay dividends.

5. Capacity Building for Permitting Agencies: Ensure that local permitting authorities (county boards, city councils, environmental agencies) have the expertise and capacity to evaluate data center projects efficiently. This might involve developing guidelines or best practices toolkits for local governments on issues like noise standards, generator emissions, and site buffering. State governments could create a technical advisory group that can assist localities reviewing a large data center proposal – helping interpret power usage plans or substation impacts. By empowering local regulators with knowledge, the process can be smoother and less prone to NIMBY opposition based on misunderstandings. Additionally, clear communication protocols between utilities and planning boards can ensure that if a new campus is proposed, everyone knows the status of grid readiness and what’s needed, preventing last-minute surprises.

6. Protecting the Public Interest: As data centers become major energy players, policymakers must ensure the public interest is safeguarded. This means continuous monitoring of reliability and resiliency – e.g., requiring that data centers above a certain size coordinate with grid emergency programs (so they don’t exacerbate an outage scenario). It also means tracking economic impacts: hold companies accountable to any job creation or investment promises made in exchange for incentives. In some cases, communities might need offset measures – e.g., if a data center’s water use is significant, maybe require investment in local water infrastructure upgrades. Essentially, policy should strive for a balanced outcome where the region gains economically from data center growth without undue sacrifice in environmental quality or grid stability.

By taking these proactive and protective measures, policymakers can create an environment where data center expansion is facilitated but also guided – ensuring the benefits (jobs, innovation, grid upgrades) flow while the risks (costs, emissions, congestion) are mitigated. This gives confidence to both the industry and the public that growth will be sustainable and well-managed.

For Investors and Financiers

1. Recognize the Market Opportunity (and Volatility): For investors – including infrastructure funds, real estate investment trusts (REITs), private equity, and bondholders – the data center energy boom represents a massive opportunity. Demand for capital will be huge: one estimate puts global data center investment needs at $1.8 trillion by 2030bcg.com, and in the U.S. tens of billions are pouring into new builds and power infrastructure. This means opportunities in financing new data center construction, acquiring and leasing facilities, funding renewable energy projects tied to data centers, and backing companies providing solutions (from cooling technology to on-site power systems). However, investors should also expect volatility and regional swings. Markets may become overbuilt then pause (if, say, too many speculative projects go up in one region), or regulatory changes could impact returns (as seen with Ohio’s tariff potentially altering data center operating costs). Savvy investors will stay informed on power availability as a key determinant of a project’s success – a gleaming new data center without adequate power is essentially a stranded asset.

2. Due Diligence on Power Risks: When evaluating data center investments (be it equity in an operator, a new development, or even loans), conduct thorough due diligence on power procurement and grid status. Key questions: Does the project have a secured power supply agreement? How robust is the local grid? Is there a risk of delays in energization? What is the power cost structure and could tariffs change? An increasing number of deals now hinge on having “at the fence” power solutions – e.g., some developers won’t break ground until the utility can guarantee capacity by a date, or they’ve arranged a dedicated substation build. Investors should scrutinize these arrangements, and possibly demand contingency plans (like requiring the project to include backup generation or an alternative feed) as part of financing conditions. Additionally, model out energy price scenarios – as data centers become 24/7 loads, they are exposed to wholesale price fluctuations (directly or via utility pass-through). If an investor is underwriting a long-term lease, understanding the lessee’s energy cost and carbon obligations is critical to assessing credit risk.

3. Embrace ESG and Sustainability as Value Drivers: Many investors today have Environmental, Social, Governance (ESG) mandates. Data centers straddle a line here: on one hand, they enable digital economy and can be very profitable; on the other, they have a heavy environmental footprint if not managed. Investors can drive value by steering investments toward operators and projects that are sustainability leaders. For instance, a data center REIT that has 100% renewable energy coverage and superior efficiency metrics may be more resilient to future regulation and enjoy lower operating costs (through energy savings) – making it a better long-term bet. Similarly, financing clean energy or energy efficiency solutions for data centers (like efficient cooling retrofits or on-site solar installations) could become a growing niche with stable returns supported by power contracts. Morgan Stanley’s analysis suggests a “large market for decarbonization solutions” is emerging around data centersdatacenterdynamics.com – e.g., companies offering waste-heat reuse, carbon capture for backup generators, or green building materials. Investors can capitalize on this by backing these solution providers or incorporating such improvements into investment assets to enhance asset value and future-proof against carbon costs.

4. Monitor Regulatory and Technological Landscape: The next 5–10 years will likely bring significant changes – from new regulations (perhaps limits on data center emissions or requirements for energy storage) to technology shifts (quantum computing? new cooling eliminating water use? etc.). Investors should keep a close watch on policy signals like the possibility of data-center-specific efficiency mandates (which could require capex for compliance but also create opportunities for firms that specialize in upgrades). Also, track technology: for example, if liquid cooling becomes standard to support AI chips, data centers without it might face obsolescence or high retrofit costs – impacting asset valuations. Or if new semiconductor tech reduces server energy consumption drastically, that could dampen power demand growth by late decade (reducing the upside for power infrastructure investments, but possibly extending life of older data centers). In essence, maintain a dynamic model of the industry rather than static assumptions. Engaging with energy analysts (the next group) and participating in industry forums can help investors anticipate these shifts.

5. Portfolio Diversification Across the Ecosystem: The interplay of data centers and power means investors can diversify within this theme. For instance, one might invest in a mix of data center assets (real estate/REITs), utility stocks or bonds in high-growth regions, renewable energy projects contracted to data centers, and technology vendors (like companies making efficient cooling systems or backup power units for data centers). This way, if one segment faces pressure (say data center REIT margins compress due to higher energy costs), another segment (utilities or renewables selling more power) might benefit – providing a hedge. Also consider geographic diversification: the U.S. trend is strong, but Europe and Asia are also seeing big data center expansions with their own dynamics (and sometimes even sharper power constraints). Global investors might allocate funds to, say, European data center development where power scarcity is a critical issue (like around London, Frankfurt, Dublin) but governments are actively intervening – which could yield interesting public-private partnership opportunities. The main idea is to balance high-growth, higher-risk bets (like a new hyperscale campus) with stable, lower-risk plays (like regulated utility returns on grid upgrades for that campus).

6. Plan for the Long Term, But Have Exit Options: Data centers, power plants, and grid infrastructure are long-lived assets (20-40 year lifespans). Investors should approach these with a long-term view on cash flows and usability. Will a data center built today still be top-tier in 2035 when perhaps AI workloads are 100x today’s? What upgrades will be needed and is there a reserve for that? Similarly, will a gas peaker plant serving data centers be at risk of early retirement due to carbon regulations in 15 years? Those considering debt financing should align loan tenors with these horizons and perhaps include covenants addressing key risks (like requiring additional borrower investments in efficiency if PUE slips). On the equity side, while long-term holds can be lucrative given the secular growth trend, one should maintain flexibility for exit if conditions change. For instance, ensure the asset could be sold or repurposed – e.g., if an area’s data center demand stagnates, can the facility be leased to another type of high-density computing (like telecom or edge computing) or sold to a different operator? Having an eye on secondary market liquidity (the pool of potential buyers down the line) is wise, because concentration risk in this sector is non-trivial (a few hyperscalers dominate demand).

In summary, investors should approach the data center power boom with excitement but also caution – rewarding those who do their homework on power risk and sustainability. By financing the right projects and companies, investors not only stand to gain substantial returns but also drive the industry toward solutions (through capital allocation choices that favor sustainability and efficiency).

For Energy Analysts and Planners

1. Refine Modeling Assumptions: Energy analysts must update their models to reflect the new realities of data center growth, which differ from past trends. Historically, many models assumed data center energy use would grow modestly or even plateau due to efficiency. That assumption may no longer hold in the age of AI. Incorporate recent data: e.g., the Berkeley Lab findings that GPU-rich servers doubled data center power use in six yearsreuters.com, or EPRI’s projection of a 10× increase in AI power by 2030spglobal.com. These suggest that load forecasts should consider high-growth scenarios where efficiency gains (while significant) are outpaced by sheer demand for computing. Analysts should consider modeling multiple scenarios (low, medium, high) for data center load, tied to key drivers like AI adoption rate, economic growth (which drives cloud adoption), and potential efficiency breakthroughs. Be transparent about assumptions – for instance, if you assume a certain PUE improvement or compute-per-watt improvement annually, state it, because this is an area of great uncertainty and debate.

2. Scenario Analysis & Uncertainty Factors: Embrace scenario planning to account for the wide uncertainty range. For example, one scenario could assume AI compute demand continues on the current exponential trajectory (a “high” case akin to 451’s forecast or DOE’s high-end), another assumes a moderation (perhaps regulatory constraints on AI energy usage or saturation of AI in the market), and a third assumes a technological breakthrough in efficiency that significantly curtails energy growth (like new chip tech or cooling eliminating most overhead). Also factor in external uncertainty factors: Will there be carbon pricing or stricter emissions rules that force data centers to limit operations or invest in on-site renewables? Could a global push for energy efficiency akin to the EU code of conduct flatten U.S. growth somewhat? On the other hand, could new sectors (edge computing, metaverse, etc.) create additional demand on top of current hyperscale trends? Analysts should stress-test the grid under these scenarios. For instance, if data center load hits the high scenario, does the planned generation build suffice? Which hours or regions become critical? This helps identify where risks of shortfall or curtailment might occur.

3. Geographic and Temporal Granularity: It’s not enough to model data center load as a national annual number – spatial and temporal granularity is key. Ensure that models capture the clustering of load in specific regions (e.g., treat Northern Virginia’s 12 GW separately from the rest of D.C./Maryland/Virginia because its impact on PJM’s local transmission is unique). Use capacity expansion and grid simulation models to see if transmission constraints bind in those areas. Temporally, consider the load shape: data centers tend to have a high load factor (i.e., nearly flat usage around the clock), which means they contribute heavily to baseload and somewhat less to peak (though still present at peak). If a lot of data center load is added, the system’s net load shape might change (flatter overnight loads, possibly higher minimum demand levels). Model interactions with renewable output – for example, if lots of solar comes on, daytime might still have surplus, but nights could see high demand from data centers that require other resources. This will influence recommendations for resource adequacy (e.g., needing more storage or flexible generation).

4. Grid Impact Studies: Energy analysts (especially those in ISOs, utilities, or consultancy roles) should conduct grid impact studies focused on data center expansion. These studies examine things like: Are new transmission corridors needed to serve emerging clusters (like central Ohio’s growth)? How will massive single-site loads (like a 1 GW campus) affect stability – do we need additional inertia or voltage support in that area? If many data centers turn to on-site generation, what does that mean for grid operations? (Could backfeeding or synchronization issues arise? Will utility planners count on those as capacity or treat them as contingency only?) One interesting aspect: 20% of data center capacity could face connection delays 2025–2030 due to grid constraints, per IEA warningsdatacenterworld.com – analysts can use such insights to advocate for specific solutions (like targeted investments or policy changes) where they see bottlenecks. Publish these findings to inform both industry and regulators.

5. Coordination with Stakeholders: As analysts, engage with both the data center industry and the energy industry to validate assumptions and get the latest intelligence. Often data center operators might not fully communicate their expansion plans to all utilities due to competitive reasons, but analysts can glean patterns from public announcements, construction pipelines, and equipment shipment data (as Berkeley Lab did using server shipment info in their reporteta.lbl.gov). Participating in forums, industry conferences (e.g., DataCenterDynamics events, IEEE forums on data center power) can help analysts ask the right questions and gather data. In turn, share analytical insights with stakeholders – for example, if a model shows that a certain region will hit a grid limit by 2026, communicate that to the local utility and economic development officials now, so they can act. Analysts might also explore bridging language and metrics: data center industry talks in terms of MW of IT load, PUE, etc., whereas power industry uses MW of peak load, MWh, etc. Translating between these (e.g., a 100 MW data center with 1.3 PUE will draw ~130 MW from grid) helps avoid confusion in planning.

6. Continuous Data Collection & Reporting: Given the fast pace, analysts should advocate for and perhaps implement continuous tracking of data center energy use. For example, the Berkeley Lab team recommended publishing the data center energy report regularly (annually or biannually)reuters.com – this kind of frequent update would greatly help calibrate models. If possible, push for better data disclosure: maybe through regulatory filings or partnerships, get aggregated statistics like total data center load per utility or state. Even an anonymized RTO-level data would be valuable (PJM, for instance, could report how much load growth in 2024 came from new data centers). With better empirical data, forecasts can be tuned. Also, track metrics like effectiveness of efficiency improvements – is average PUE actually dropping year over year? Are server utilizations improving or is the industry still adding capacity faster than it can optimize usage? These metrics influence future consumption.

7. Integrate Data Centers into Energy Transition Models: Finally, incorporate data centers into the broader context of the energy transition. As analysts, consider that at the same time data center load is growing, other sectors (transportation electrification, electrified heating, hydrogen production) are also adding load, while generation mix is shifting to renewables. Integrated resource planning should not treat data centers as an isolated anomaly but as a key element of future load that may also offer some flexibility or resources (if they deploy storage, etc.). For example, some have floated ideas like “could data centers become hubs for community energy, hosting large batteries that also support the grid?” or “could their generators be leveraged in emergencies?”. Analysts can quantify potential benefits of such integrations. Also, explore coupling: data centers might pair with desalination or other processes to utilize waste heat or adjust load. These innovative concepts require analytical vetting to see if they hold technical and economic merit. By situating data center demand within the whole system’s evolution, analysts can give more nuanced guidance: e.g., maybe encourage a future where data centers act as anchor loads that justify new clean power plants which also serve the public.

In summary, energy analysts are the scouts and map-makers for navigating the data center demand surge. By improving data and models, exploring uncertainties, and actively communicating with industry and policymakers, analysts can ensure that our understanding stays current and that plans remain robust under different futures. The work of analysts will be critical in preventing under- or over-building and in highlighting the most cost-effective, resilient path to integrating these massive new loads.

Conclusion

The projected increase in U.S. data center grid-power demand through 2030 is nothing short of transformative. In the span of a decade, data centers are moving from a niche portion of electricity consumption to a top-tier driver of load growth, fueled by our insatiable appetite for digital services and the dawn of AI-driven computing. Opportunities abound – for innovation, investment, and efficiency gains – but so do risks that, if unaddressed, could hinder not only data center expansion but also broader energy reliability and climate goals.

Each stakeholder has a crucial role to play in this journey. Data center operators must evolve beyond being just tech landlords to becoming sophisticated energy managers, embracing sustainability and grid synergy as core parts of their business. Policymakers and regulators are tasked with threading the needle: facilitating infrastructure and economic growth on one hand, while safeguarding public interests and steering the sector toward societal objectives (like decarbonization and equitable cost-sharing) on the other. Investors hold the purse strings that will fund this expansion – their choices can accelerate smart, green data center growth or, if misdirected, contribute to bubbles and unsustainable practices. And energy analysts and planners provide the guiding intelligence, ensuring decisions are data-driven and foresightful, rather than reactive.

The risks discussed – grid congestion, emissions, speculative load, cost burdens, permitting logjams – are formidable. Yet, the solutions are within reach. In many cases, the industry is already responding: we see data center firms investing in renewables and microgridsspglobal.comdatacenterdynamics.com; utilities proposing novel tariffs and capacity plansspglobal.comspglobal.com; and governments starting to strategize around this new realityreuters.com. The challenge is to scale up these responses, share best practices, and avoid siloed thinking. A sustainable path will involve cross-sector collaboration – tech companies working hand-in-hand with energy providers and regulators to design the digital-electric ecosystems of the future.

Crucially, pursuing a sustainable growth trajectory for data center power is not just risk mitigation – it’s an opportunity to modernize our energy infrastructure and drive innovation. Data centers could become key enablers of grid modernization: their constant demand can anchor new clean energy projects; their sophisticated controls can provide grid services; their capital investment can revitalize regions and fund new technologies. In essence, if managed properly, the data center boom can align with the push for a smarter, greener grid, to the benefit of all.

The period through 2030 will set the tone. By the end of this decade, we will either be telling a success story of how exponential digital growth was balanced with sustainable practices – or we will be grappling with the fallout of neglected constraints. This white paper has outlined the critical issues and offered a framework of solutions tailored to each major stakeholder. The evidence and forecasts from S&P Global, 451 Research, DOE, IEA, and others are clear about the trend; now it falls to industry leaders, government officials, financiers, and analysts to act on this knowledge.

In conclusion, the coming surge in data center power demand is both a test and an opportunity for the U.S. energy system. By understanding the risks and proactively implementing the strategies discussed – from robust planning and policy to innovation in operations and technology – we can ensure that the growth of our digital infrastructure is empowered by sustainable, reliable energy infrastructure. With foresight and cooperation, the U.S. can meet the data center demand boom head-on, powering the digital economy of 2030 in a way that is resilient, clean, and beneficial for all stakeholders. The time to prepare is now, while the curve is still on the rise and before constraints bite – so that come 2030, we look back on a decade of well-managed growth and shared success.

References

- 451 Research / S&P Global Market Intelligence forecast data, as reported in S&P Global Commodity Insights (Oct 2025)spglobal.comspglobal.com and summarized by DCDdatacenterdynamics.comdatacenterdynamics.com.

- Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory & U.S. DOE, 2024 United States Data Center Energy Usage Report, findings reported by Reuters (Dec 2024)reuters.comreuters.com.

- Reuters Events Industry Insight, Big Tech, power grids take action to rein in surging demand (Aug 2025) – DOE forecast of 20 GW new load, data centers 6.7–12% of U.S. power by 2028reuters.comreuters.com; Dominion Energy high-load rate class and 40 GW under contractreuters.com.

- DataCenterKnowledge, Why Data Center Grid Connections Are Slowing Down (Mar 2025) – Virginia grid connection delays up to 7 yearsdatacenterknowledge.com, need for careful site selection and on-site generationdatacenterknowledge.com.

- DataCenterDynamics, S&P Global: US data centers to require 22% more grid power by end of 2025 (Oct 2025) – State-by-state demand projections (VA 12.1 GW, TX 9.7 GW in 2025)datacenterdynamics.comdatacenterdynamics.com; growth in secondary markets and on-site power trend in Permian TXdatacenterdynamics.comdatacenterdynamics.com.

- Morgan Stanley Research via DCD, Data center industry will emit 2.5bn tons of CO2 by 2030 (Sep 2024) – Emissions projection and hyperscalers’ clean energy investmentsdatacenterdynamics.comdatacenterdynamics.com.

- Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) report (Aug 2025) via S&P Global – AI power demand could top 50 GW by 2030, with single AI training runs hitting 1–2 GW by 2028spglobal.comspglobal.com.

- International Energy Agency (IEA) commentary – data center electricity use worldwide set to double to ~945 TWh by 2030, driven by AIdatacentremagazine.com.

- Energy and Environmental Economics (E3) report for Virginia (2023) – warning that infrastructure development pace will constrain data center growthreuters.com.

- American Electric Power (AEP) data center tariff in Ohio – Public Utilities Commission of Ohio ruling (July 2023) requiring 85% payment for subscribed capacityspglobal.comspglobal.com, resulting in pipeline reductiondatacenterdynamics.com.

- PJM and ERCOT market rule changes – Reuters (Aug 2025) noting PJM capacity auctions and CAISO demand response for hyperscale loadsreuters.com, ERCOT ride-through requirements and high price cap incentivesreuters.com.

- Microsoft and Meta renewable energy procurement – Morgan Stanley/DCD noting Microsoft’s 34 GW of renewable capacity procureddatacenterdynamics.com and Meta’s 2025 nuclear PPA in Illinois (DCD, June 2025)datacenterdynamics.com.

- McKinsey & Co., The cost of compute: $7 trillion race to scale data centers (2023) – global investment needs by 2030mckinsey.com.

- CBRE IM, By 2030, data centers could account for 7.5% of U.S. electricity consumption (2024)cbreim.com.