Designing a Post‑Labor Economy in the Age of AGI and Robotics

By Thorsten Meyer AI

The world is walking into a contradiction: we are building machines that can create more value with fewer humans, faster than our institutions can adapt. On paper, that should be the greatest prosperity engine in history. In practice, it collides head‑on with a hidden assumption baked into modern capitalism: most people get purchasing power by selling their time. Wages aren’t just a reward for work—they’re the primary pipe that delivers money to households so demand can exist at scale.

When automation becomes good enough and cheap enough, that pipe narrows. Not because anyone “hates workers,” but because every competitive incentive points to replacing human labor with systems that are faster, safer, and more reliable. The result is a system that can produce abundance while starving its own customer base. You can’t run an economy on productivity alone. You need velocity—money circulating through households, not pooling exclusively around ownership.

This is where the Great Rewiring begins: a shift from a labor‑mediated economy (income primarily through jobs) to a capital‑mediated economy (income primarily through broad ownership). In a post‑labor world, the central question is not whether we can produce enough. We will. The real question is whether the gains from automation are structured to flow back to the population—systematically, predictably, and with minimal friction—so people remain empowered participants in the economy rather than spectators.

What follows is a comprehensive blueprint for that transition: why the wage‑based economy breaks under extreme automation, how dividends can replace wages as the stabilizing floor of demand, why payment rails become critical national infrastructure, how taxation must track value creation as labor shrinks, and what it means to build a society where dignity and contribution aren’t measured solely by employment.

1) The hidden engine of modern prosperity: the wage loop

Most debates about AI and jobs focus on production: “Can machines do the work?” But the larger issue is distribution: “How does the money reach people so they can buy what’s produced?”

In today’s economy, the distribution mechanism is mostly employment.

- Businesses hire people and pay wages.

- People use wages to pay rent, buy food, purchase services, and support families.

- Businesses receive revenue and keep hiring.

- Governments tax wages to fund services and infrastructure.

This cycle is so normal that we treat it like nature. It isn’t. It’s an institutional design: a social contract that made sense when human labor was the bottleneck of production.

Now the bottleneck is shifting.

2) Why advanced automation breaks the cycle

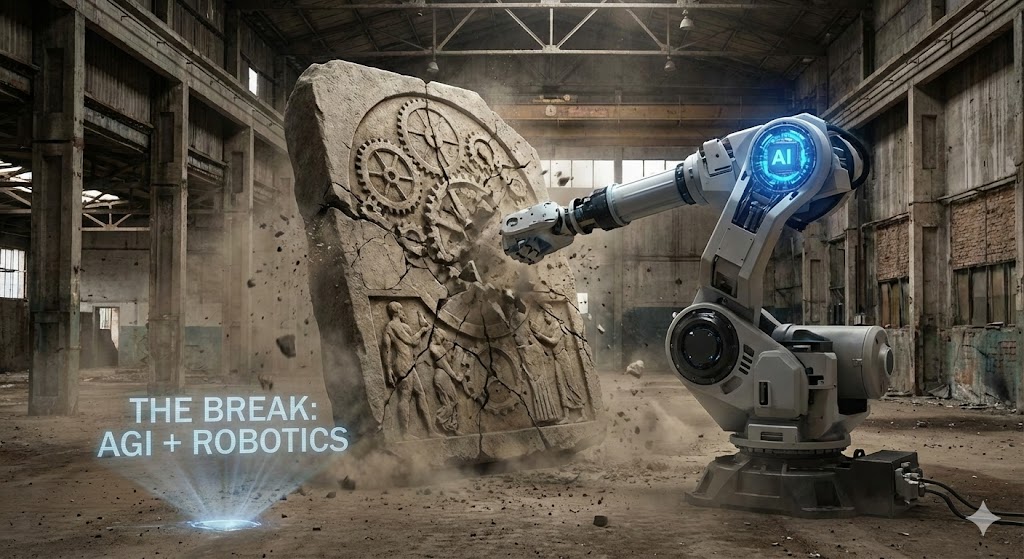

Automation has always replaced certain tasks. The difference now is scope.

For the first time, software systems are rapidly encroaching on work that used to be “human by default”: writing, summarizing, advising, planning, customer support, analysis, coding, design, even elements of management. Pair that with robotics—machines that can move, manipulate, drive, clean, build—and you get a powerful convergence:

- Cognitive labor gets cheaper and faster through AI.

- Physical labor gets cheaper and safer through robotics.

- Coordination and optimization improve through autonomous systems that manage workflows end‑to‑end.

As soon as an automated solution becomes more cost‑effective than hiring humans, firms face intense pressure to adopt it. Not adopting automation becomes a competitive disadvantage—like refusing to use electricity because candles feel more familiar.

This is why job disruption is not just about a few sectors. It becomes systemic when three things happen at once:

- Automation handles a large portion of economically valuable tasks.

- Automated firms scale with minimal headcount.

- The biggest winners reinvest profits into more automation, compounding the advantage.

At that point, a wage‑dependent economy runs into a hard constraint: wages shrink faster than consumption needs.

And then demand becomes the problem.

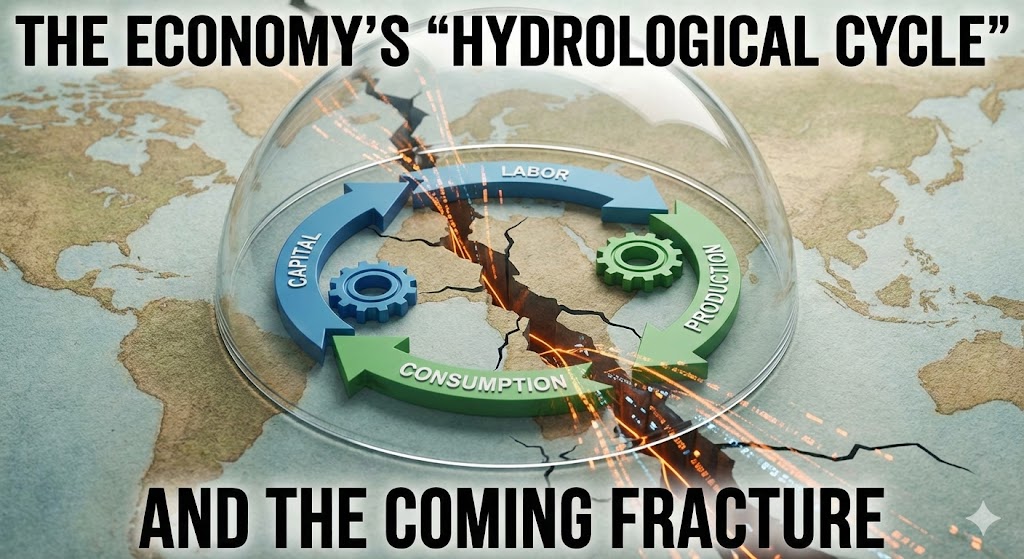

3) The economy as a circulation system, not a scoreboard

A useful way to think about the economy is as a circulation system—like a city’s water grid or a power grid. The goal isn’t to “produce the most” in the abstract. The goal is to keep essential flows stable:

- purchasing power to households,

- spending into goods and services,

- revenue back to firms,

- taxes to maintain public infrastructure,

- investment into the next cycle.

When the distribution pipe narrows, production can still grow—but society can still destabilize.

This is why “GDP up, employment down” is not automatically good news. An economy can become incredibly productive while simultaneously becoming socially brittle, politically volatile, and financially unstable—because the output isn’t matched by widely distributed purchasing power.

In extreme form, you end up with a paradox:

- The system can produce abundance.

- But the system can’t reliably convert abundance into broad well‑being.

That isn’t a technology problem. It’s a plumbing problem.

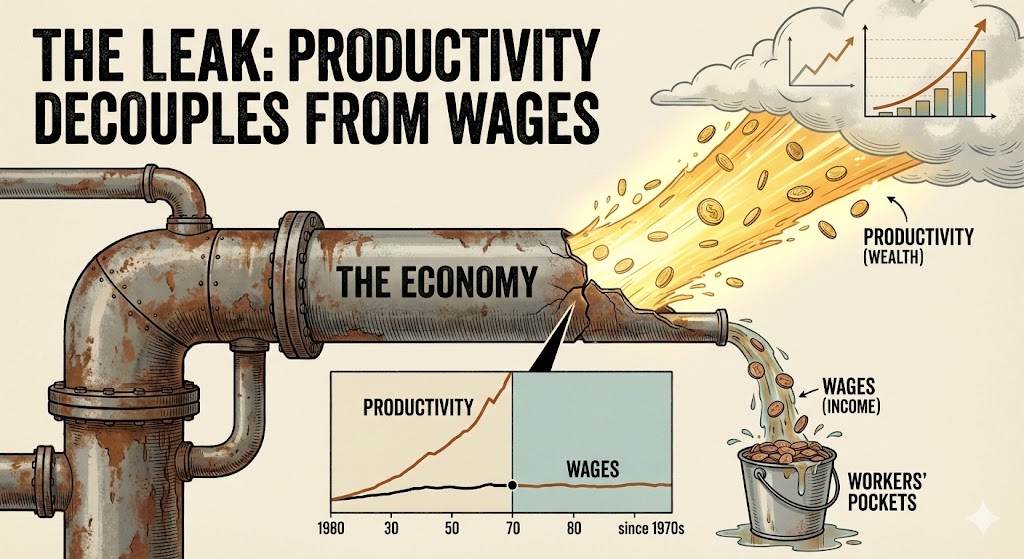

4) The prequel we’re already living: the productivity‑wage gap

Long before the arrival of advanced AI, many societies saw signs of strain:

- productivity rising faster than typical wages,

- wealth concentrating around asset owners,

- housing and healthcare costs outpacing incomes,

- a growing reliance on consumer debt and asset inflation,

- political polarization fueled by economic insecurity.

This matters because the post‑labor transition doesn’t start from a healthy baseline. It starts from an economy where many households already feel like they’re running in place.

Historically, there have been periods where innovation expanded output without improving median living standards for a long time (a dynamic sometimes compared to early industrialization). That history tells us something crucial:

Technology does not automatically distribute its benefits.

Distribution is a policy and ownership question.

Which brings us to the core redesign.

5) The Great Rewiring: from labor‑mediated to capital‑mediated income

If wages become a smaller share of total income, the economic system needs a new primary distribution channel.

The Great Rewiring is the idea that ownership must replace wages as the default claim people have on economic output. In other words:

- In a labor‑mediated economy, most people get income because they work for someone.

- In a capital‑mediated economy, most people get income because they own a share of the productive engine.

This doesn’t mean nobody works. It means survival and basic security are no longer conditional on selling labor into a market that needs less of it.

A post‑labor economy is not “a world without effort.” It is a world where employment is optional for survival and work becomes increasingly about meaning, creativity, status, craft, service, and ambition—not merely rent payment.

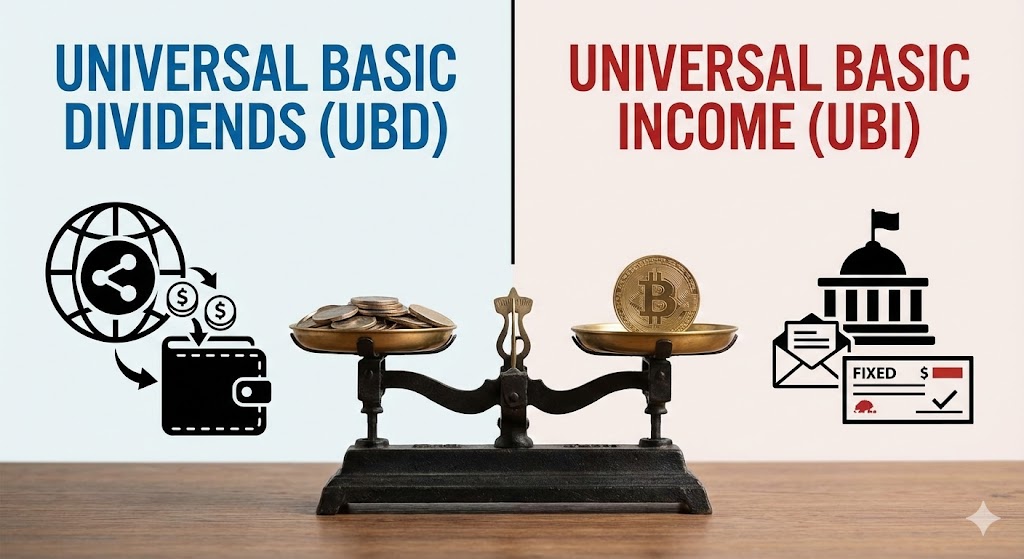

6) The dividend society: universal basic dividends, not just “handouts”

The most realistic way to turn broad ownership into broad income is dividends.

Think of the automated economy as consisting of high‑value productive assets:

- compute (data centers, chips, model infrastructure),

- energy (solar, nuclear, grid modernization),

- robotics and autonomous fleets,

- automated manufacturing and logistics,

- industrial software systems that coordinate production.

These assets will generate cash flows—directly or indirectly—through the goods and services they make possible. The question is: Who captures those cash flows?

A dividend model says: capture a portion into public or broadly shared vehicles, then distribute returns to people as:

- a monthly dividend,

- or a quarterly payment,

- or a hybrid “base dividend + stabilization bonus” in downturns.

Why dividends matter politically and psychologically:

- Dividends feel like ownership, not charity.

- They’re easier to defend because they are framed as “my share of the system I belong to.”

- They scale naturally with productivity: as the automated economy grows, the dividend can grow.

This shifts the social contract from “earn your right to consume” to “own your share of the productive commons.”

7) Where do the dividends come from? Funding the new social contract

A post‑labor dividend system has to be grounded in real revenue streams. There isn’t one magic funding source. The likely future is a portfolio approach—just like any serious investment strategy.

Here are the major buckets that can seed and sustain a dividend model:

A) Sovereign or public wealth funds

Governments can create funds that invest in diversified assets—global equities, infrastructure, strategic national projects—and distribute a portion of returns to citizens. Some countries already use versions of this logic with resource revenues. The post‑labor shift expands the concept to the “resources” of the digital era: compute, energy, and automation rents.

B) Automation and compute rents

As AI becomes foundational infrastructure, certain choke points may generate outsized rents:

- access to high‑end compute,

- energy supply for data centers,

- licensing of critical models and datasets,

- dominant distribution channels.

If these rents remain private and concentrated, inequality accelerates. If a portion is captured (through taxes, licensing frameworks, or public stakes), it becomes a sustainable base for dividends.

C) Land value capture and location rents

Land is not produced by markets; it is a foundational input. As automation changes labor patterns and cities, capturing location rents can fund public services and dividends while discouraging speculative hoarding.

D) Consumption and value‑added taxation—with rebates

Consumption taxes can be efficient but regressive. In a dividend society, a consumption tax can be paired with a dividend rebate so the net effect is progressive: the baseline dividend offsets the tax burden for most households.

E) Carbon and resource taxes

Compute and robotics will be energy intensive. Carbon pricing and resource taxation can simultaneously encourage sustainability and fund public claims on the productivity of the automated economy.

The principle is simple:

As labor becomes less central to value creation, the funding base must shift to where value actually concentrates.

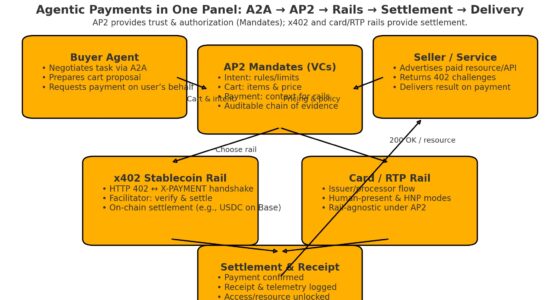

8) Payment rails: the new “roads and bridges” of demand

A dividend model succeeds or fails on distribution efficiency.

If money movement is slow, expensive, or captured by middlemen, then the system leaks value and breeds resentment. In a post‑labor world, payments infrastructure isn’t just finance—it is macroeconomic stability infrastructure.

The best examples of modern payment design treat money movement like a public utility:

- real-time transfers,

- interoperability across banks and apps,

- low fees and universal access,

- strong fraud prevention and dispute resolution.

In short: the economic system needs pipes that don’t clog.

A serious Great Rewiring agenda includes:

- real-time payment systems that reach everyone,

- digital identity that is secure and privacy-preserving,

- simple citizen wallets with offline options,

- anti-fraud systems that don’t punish honest users,

- transparent governance so payment rails don’t become surveillance rails.

Because if dividends are the new wages, this is the payroll system for society.

9) The tax shift: from payroll to capital, land, and rents

Most governments are funded through mechanisms designed for a job-centered economy:

- income taxes,

- payroll taxes,

- employer-based contributions tied to labor.

As labor income shrinks, those instruments weaken. Governments then face a choice:

- cut services and destabilize society, or

- redesign taxation to align with the automated economy.

A post‑labor tax base typically leans on:

- capital income and large-scale profits,

- land and property value capture,

- consumption (with progressive rebates),

- environmental externalities,

- monopoly rents from concentrated markets.

A key nuance: this is not about punishing success. It’s about preventing the automation dividend from being privately captured while society absorbs the adjustment costs.

If the public pays for education, infrastructure, stability, and the rule of law—then the public needs a durable claim on the wealth those systems enable.

10) Competition, monopoly, and the ownership question

The Great Rewiring is ultimately an ownership debate.

If automation leads to “winner-take-most” markets—where a few firms dominate compute, models, distribution, and data—then even a good dividend policy can struggle. Why? Because concentrated players can lobby, influence regulation, and shape the terms of distribution.

A serious post‑labor strategy must include:

- stronger antitrust capacity,

- interoperability requirements,

- open standards where appropriate,

- procurement policy that prevents lock-in,

- public alternatives in foundational layers (especially payments and identity),

- guardrails against regulatory capture.

In a world where capital is the primary income source, monopoly becomes a direct threat to democracy.

11) The human role in a post‑labor world: demand, meaning, and dignity

One of the worst ideas circulating in tech discourse is that people become economically irrelevant once machines are productive enough. That view is both ethically toxic and economically incoherent.

Humans remain essential as the purpose of the system

Economies do not exist to maximize output. They exist to support human lives. If automation increases output, that is only meaningful if it increases well‑being.

Humans remain essential as the demand signal

Even in a highly automated system, someone must decide:

- what matters,

- what should be prioritized,

- what risks are acceptable,

- what “good” looks like.

Machines optimize. Humans value.

The meaning challenge is real

Jobs provide more than income:

- routine,

- identity,

- social status,

- community,

- a sense of contribution.

A dividend society cannot ignore that. The Great Rewiring is not only economic; it is cultural.

A post‑labor society must actively invest in:

- education that emphasizes creativity, ethics, and systems thinking,

- civic institutions that organize purpose outside employment,

- community-based projects and care networks,

- arts, science, and entrepreneurship as public priorities,

- mental health infrastructure and social cohesion.

Dividends can stabilize demand. They do not automatically stabilize identity.

12) Three futures: where we land depends on design

Automation doesn’t guarantee one outcome. It creates a fork in the road. Here are three simplified futures:

1) Dividend Renaissance (broad ownership)

- Automated productivity grows rapidly.

- Public or shared ownership captures a portion of returns.

- Dividends rise with productivity.

- Poverty collapses and consumption stays stable.

- People shift into creation, care, learning, and entrepreneurship.

2) Neo‑Feudal Automation (concentrated ownership)

- A small class owns the productive engine.

- Wages stagnate or collapse for the majority.

- Transfers are minimal and politically contested.

- Demand becomes fragile; instability rises.

- Surveillance and coercive control expand to manage unrest.

3) Managed Transition (messy middle)

- Partial dividends + partial wage economy.

- Long period of turbulence and experimentation.

- Regions and countries diverge in outcomes.

- The social contract is renegotiated repeatedly under pressure.

The Great Rewiring is about maximizing the odds of Scenario 1 and avoiding Scenario 2.

13) A practical blueprint: how to implement the Great Rewiring

This is the part most people skip. Big ideas are easy. Implementation is the hard work.

Step 1: Create an Automation Dividend Fund

A national or regional public wealth vehicle seeded by a portfolio of revenue streams:

- automation rents, excess profits, and capital taxes,

- land value capture,

- carbon/resource taxes linked to compute and logistics,

- strategic public stakes in critical infrastructure.

Design principles:

- independent governance (protected from short-term politics),

- transparent reporting,

- clear distribution rules,

- anti-corruption safeguards,

- long-term investment mandate.

Step 2: Build real-time distribution infrastructure

Treat payments like a public utility:

- instant transfers,

- universal access,

- privacy-preserving identity,

- strong anti-fraud design,

- low or zero fees for citizens.

This is not “fintech.” This is economic stability infrastructure.

Step 3: Redesign the tax base for an automated economy

Shift away from heavy dependence on payroll taxes toward:

- capital and rent capture,

- consumption taxes paired with dividends,

- land and property reforms,

- environmental and resource pricing.

The goal is alignment: tax where value concentrates, recycle into broad purchasing power.

Step 4: Expand ownership beyond the state

Governments aren’t the only path. Encourage:

- employee ownership and profit-sharing that persists even as headcount shrinks,

- cooperative ownership models in local automation projects,

- consumer membership structures (“users as stakeholders”),

- community-owned energy and infrastructure.

A healthy post‑labor transition uses both top‑down and bottom‑up ownership expansion.

Step 5: Build the culture of contribution beyond employment

A society that divorces survival from jobs must build new prestige ladders:

- civic contribution,

- caregiving and community building,

- mentorship, art, science, open-source work,

- entrepreneurship, craftsmanship, and local problem solving.

We should not pretend this happens automatically. It must be designed and nurtured.

14) What to do now: a pre‑rewiring playbook

The transition doesn’t start “someday.” It starts as soon as automation meaningfully reshapes hiring, wages, and business models.

For policymakers

- pilot dividend mechanisms tied to real assets (not just deficit spending),

- modernize payment rails and digital identity with privacy safeguards,

- invest in energy + compute as strategic infrastructure,

- strengthen antitrust and interoperability rules,

- update tax systems to reduce avoidance and capture rents,

- treat the post‑labor debate as infrastructure planning, not ideology.

For businesses

- model demand risk: “If we automate aggressively, who buys the output?”

- implement profit-sharing and ownership programs to stabilize trust and legitimacy,

- invest in roles that amplify human experience (trust, community, design, care),

- be transparent about automation strategy to reduce backlash,

- build products that make life better, not just cheaper.

For individuals

- move from “job security” to “resilience strategy,”

- learn AI literacy at a conceptual level (how systems work, where limits are),

- build assets where possible (savings, diversified investments, equity exposure),

- develop durable skills: framing problems, leadership, taste, ethics, relationships,

- invest in community—social capital becomes critical in turbulent transitions.

Conclusion: the future will be automated—prosperity is a design choice

A post‑labor economy isn’t a sci‑fi fantasy. It’s what happens when the marginal cost of doing work keeps falling—first in software, then in services, then across the physical world. The only uncertainty is whether we treat that shift as a deliberate redesign or sleepwalk into it and let outdated incentives decide the outcome.

The Great Rewiring comes down to three fundamentals:

- Ownership: If automated assets remain narrowly owned, automation amplifies inequality and destabilizes demand. If ownership is broadened—through public funds, shared infrastructure stakes, and durable dividend mechanisms—automation becomes a compounding engine for mass prosperity.

- Plumbing: Dividends and modern distribution aren’t just policy choices; they’re delivery systems. Frictionless payment rails, low leakage, strong anti-fraud design, and universal access are not “nice to have.” They are the infrastructure that keeps economic velocity alive when wages are no longer the main distribution channel.

- Purpose: Even if survival is guaranteed, a society still needs meaning. The job economy accidentally solved for identity, structure, and status. A post‑labor world must solve it intentionally—through education, community, creativity, caregiving, entrepreneurship, and civic contribution.

The decisive question is simple and unavoidable: Who owns the productive engine of the automated age, and how do its returns reach everyone? If we answer that with systems—funds, rails, rules, and culture—automation becomes liberation: more security, more choice, more human flourishing. If we don’t, we get abundance trapped behind ownership walls, and a population asked to compete for scraps in an economy that no longer needs most of its labor.

The future will be automated. Whether it will also be stable and widely prosperous is not a matter of technology. It’s a matter of design.